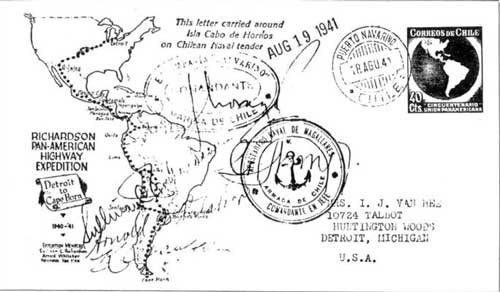

The Richardson Pan-American Expedition

This story originally appeared in issues 135, 136 and 137 of the Plymouth Bulletin (1982)

Prologue by Jim Benjaminson

For every story that appears in the Bulletin, there is a story behind the story.

The Richardson Pan-American Highway Expedition is perhaps one of the greatest automotive stones of all time. In scope and magnitude, it surpasses those pioneer automobilists that first crossed the United States at the turn of the century The Richardson Expedition crossed not only this country but encompassed the area spanning two continents, crossing trackless wilderness, endless mud, unchartered territory, and obstacles of every sort that Mother Nature could throw against them.

The men of the expedition, Sullivan C Richardson, Arnold Whitaker, and Kenneth C. Van Hee, were many times called "Three Damn Fools" by friends and foes alike. It is a title that was perhaps fitting, considering the almost insurmountable odds against their succeeding—but succeed they did—and now that title is worn proudly.

The Richardson Pan American Highway Expedition was perhaps the last great automotive adventure undertaken on the face of this earth.

The "story behind the story" of our publication of their account begins with three other men, forty-one years after the expedition set out from Detroit that cold November morning. It starts on a warm, sunny North Dakota afternoon as these three, Mel Stark, Richard Thurston, and Bulletin editor Jim Benjaminson, headed into Canada on a business trip. While in Canada it was only natural for Benjaminson to wander into an automotive supply store and check out the magazine rack. That resulted in the purchase of Petersen Publishing Company's Second Edition of Plymouth Dodge-Chrysler book.

Among the articles was "Cape Horn Caper", which gave a few details of the Richardson Expedition with a few photographs of their 1941 Plymouth sedan. The article stated that expedition leader Sullivan Richardson had written a book, entitled Adventure South, but Petersen Publishing had been unable to locate the author or the publisher, so they could not reprint any of the book’s material.

One photo caption indicated Chrysler executives had been questioned about the car but the only reply was that they felt the car was still somewhere in Central or South America; yet the photographs of the car taken after the Trip showed it with 1945 Illinois license plates and a gas ration sucker. To the intrepid Bulletin editor, that meant the car HAD to have returned to the United States. This lead to plans to locate any living members of the Richardson Expedition.

The trail began with the car's 1945 Illinois license plate, number 752-534. Benjaminson contacted Plymouth Club member Pat O'Connor, who is an Illinois state trooper. Could that 1945 license plate number be traced? Pat contacted the office of the Illinois Secretary of State, who in turn dug into the records. On February 11th, 1982, the search showed that it was registered to S. C. Richardson, with an address; the car was listed as a 1941 Plymouth 4 door sedan, serial No. 15031250, engine number P11-214804. The address was, of course, 37 years old but it was a place to start.

From that point Ron and Joan MacKenzie, also Plymouth Club members from Oak Lawn, Illinois were contacted. Would it be possible for them to go to that address and see who or what they found? The MacKenzies leaped into the search but Sullivan Richardson was not to be found.

Expedition members in front of the Detroit News.

As the Expedition had begun in Detroit it was only logical to also check the Detroit area. Club vice-president Joe Suminski joined the detective’s list. He found a party that had photographed the battered Plymouth in a Detroit parade in 1946, but once again the trail went cold.

Long distance information was used in the Chicago and Detroit areas to attempt to locate any of the Expedition members, but the only lead, an A. Whitaker listed in the Detroit phone book, proved to be a false alarm.

It appeared the search was at an end; then the MacKenzies tried one last source-—the Action Line column of the Chicago Tribune. The date was March 25th.

On April 19th, Mrs. Elva Richardson penned the following note to the Chicago Tribune's Action Line: "A friend living in Chicago sent us a clipping from your March 25th column; all three of the men are living in Southern California."

Success—with a capital "S"! The search for Sullivan Richardson, Arnold Whitaker and Kenneth Van Hee was at an end. All of the men have been contacted, many questions have been answered about the trip, and many original photographs were borrowed. Best of all, Sullivan Richardson agreed to have portions of his book Adventure South to be reprinted in the Bulletin's 25th Anniversary issue.

Adventure South - By Sullivan C. Richardson

On Sunday, November 17, 1940, the Detroit News ran this eight-column head: "Detroit Expedition Ready To Blaze Auto Trail To Cape Horn."

"To cross 14,000 miles of North and South America", ran the opening paragraph, "through tremendous expanses of jungle and over high mountains is the ambitious undertaking of the Pan American Highway Expedition, which will leave Detroit tomorrow to attempt what nobody has ever done-drive an automobile all the way from the United States, over the proposed route of the Pan American Highway, to the lower end of South America."

"The expedition will be headed by Sullivan C. Richardson, a Detroit News advertising man He will be accompanied on this adventure by Arnold Whitaker specialized mechanic from one of Detroit's big automobile plants ... and Kenneth C. Van Hee, also of Detroit ... They will drive a 1941 stock model Plymouth automobile, built in Detroit."

Two small boats were lashed to a rail to provide a platform for the expedition car.

Across the country from Washington to Los Angeles, people scarcely raised an eyebrow at the announcement. Those unacquainted with the geography of the Southern Americas and previous attempts to take an automobile through them, were unimpressed. Those who did know simply said it couldn't be done and dismissed the expedition as another stunt by "publicity hounds who'd do anything to get their names in the papers" and who'd "give up when they hit the first hard stretch."

The "Cape Horn Auto Caravan will bog down," said Harry Chandler, the publisher of the Los Angeles Times in a two-column interview by Editor & Publisher on December 28. "If the Detroiters can make it to the Pacific port of Panama and ferry to a landing on solid roadbed in Colombia, they should be able, weather conditions permitting, to finish their journey to Argentina's capital city. That 'if' remains formidable." And Mr. Chandler was "pretty certain" the expedition would never get through Central America.

He was not alone in his conviction. American Automobile Association directors, Pan American Union and Highway Confederation officials and engineers, business men and intimate friends of expedition members from Detroit to New York, joined in the publisher's opinion with varying degrees of vehemence.

"You're three damn fools," we were told, too often to fight about it. And we offered little or no denial. In fact we had no tangible evidence on which to base denial. Still we wanted to go. We'd make every possible preparation for road trouble: we'd be vaccinated for typhoid, yellow fever, small pox and diphtheria. We'd carry quinine for malaria; we'd boil all water we drank and be careful about fresh vegetables and fruits as carriers of the dread amoebic dysentery: in short, we'd do all three men could do, then hope for breaks when the going got beyond us. It sounded sufficient to the expedition.

A few minutes before midnight, Monday, November 18th, we drove quietly out of Detroit and headed southwest. We were off the great adventure. How great, we were happily ignorant. It was enough that we were started.

Even as we rolled along through the night over the smooth pavement of U.S. 112 to Chicago, we recalled and chatted about the advices we had received from United States diplomatic representatives throughout Central and South America. Acting on instructions from the State Department in Washington, these representatives had helpfully furnished us information and data. In friendly, but pointed terms, they suggested we call the whole thing off.

Meredith Nicholson, American Minister to Managua, wrote: "So far as I am aware, no individual has been able to make the trip from one boundary of Nicaragua to the other all the way by automobile. Last year a fully equipped expedition, which had traversed the Sahara three times and had gone from end to end of Africa, was compelled to abandon the attempt after progressing from the northern Nicaraguan line to the town of Chinandega. Hospitalization was also necessary."

"There is no road," wrote Spurille Braden, American Ambassador to Bogotá, Colombia, in his letter of October 30th. "T6,; line shown on the highway map is only a projected highway on which no construction has been done ... In the Embassy's opinion and in that of the Ministry of Public Works (Colombia), it would be folly to attempt to cross that territory in an automobile."

"From Cartago to the Panama line you will have your greatest and perhaps insurmountable difficulties," came from E. W. James, Chief of Highway Transport, Division of Public Roads, Washington. "I have no hope you can get through."

We had never intended to try crossing the unbroken swamps, mountain and jungle terrain of the Darien Peninsula from the Panama Canal to Turbo in Northern Colombia. There is not even a footpath through that wilderness, and the Atrato River Basin spreads a hundred miles of death filled swamp between Darien's neck and the little hamlet of Turbo on the eastern coast of Darien Gulf to which point Colombia is projecting a highway down from Paravandocito. We would be satisfied actually to reach the Canal with the car, then ferry to "solid ground" in Colombia, as the Los Angeles Times' Mr. Chandler had suggested. But we weren't going to stop with Argentina's capital. Our destination was Cape Horn. And the car must actually reach Magellan Straits!

"That's a long way south," said Arnold as we rolled up and down Michigan's Irish Hills. It wasn't hard to keep awake, even in those hours from midnight to dawn.

"If we reach Cape Horn," I replied, "we'll only be 500 miles from Byrd's Little America, according to the map."

"If we get that close," Ken put in, "we ought to-"

"Cape Horn's far enough. Richard and the penguins can keep Little America. We'll probably be ready to start north once we round the Cape." I straightened my back to dislodge a "driving hitch" in the back of my neck. We'd probably have a lot of them in the next 15,000 miles.

We fell silent. The purr of the motor was comforting. Would it always respond so nicely in the months ahead? Time would write that chapter: Time, and Arnold's solid capable hands.

Even during those first hours of the trip, too, we discussed the west coast of Mexico and what S.L.A. Marshall, Detroit News' war analyst and authority on Mexican affairs, had said about it.

"Why kill the expedition before it gets started, Rich?" he had asked quietly. "Take the paved Pan American Highway from Laredo to Mexico City, and leave the west coast alone. That's not the Pan American, anyhow."

Mules were used to cross rivers and streams; note the upswept exhaust pipe.

"There's no road—for tourists. A few dry-weather trails, stretches for trucking and bits of roads near towns. Save your punches and go the easy way. You'll need all the guts you've got." Sam Marshall eyed me soberly. "If you hit rain, it'll stop you. Mexico mud is hell."

Leaving Mesa, Arizona, we stopped at a farmers' Weighing-in Station, and drove our car onto the big scales. We were fully loaded: three men, fifty gallons of gasoline, five gallons of water, and all regular equipment. There was no back seat in the car. It had been omitted at the factory to make room for beds, folding cots, duffle bags, tent, rubber boat, car replacements, camera equipment, boxes of film, suitcases, food, cookstove, etc. And atop the car, anchored on a platform bolted directly to the steel posts of the car body, rode two extra wheels and tires, 300 feet of rope, two sets of block and tackle, two axes. a steel bar, shovel, hoe and pick: our preparation for rough going.

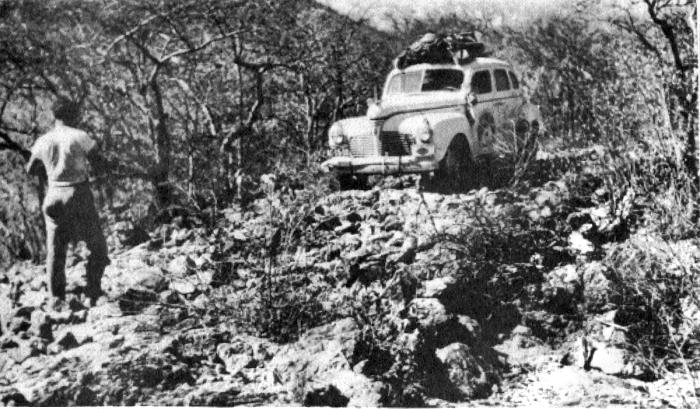

Making their own trail through trackless wilderness south of Oaxaca.

This 50-mile stretch took 25 days to cross.

"What does she tip at?" we called.

"Fifty-six thirty. Quite a load for one motor to take to Cape Horn."

"You're not just saying it, brother!" Whitaker grunted from his side of the front seat. He shoved bus head dawn for a look at the fire extinguisher to be sure we hadn't forgotten it. Then he growled to Kenneth and me. "Three tons. And we expect to take it through swamps." It sounded like prophecy.

The motor started with a roar and we drove out of Mesa. There was no further discussion of tons or swamps. That was future.

We'd soon be out of the United States and started on that long trek through strange places and circumstances. Perhaps actual realization of it was finally working into our consciousness.

"What we get across that line over there." I said, throwing a thumb in the direction of the international border a few blocks away, "I'm going to forget that such a thing as time exists."

"Of course," Ken said without looking my way, "Time, and the return to Detroit next July." It sounded like more prophecy. We expected the trip to take six or seven months and had been working against dates and normal rainy-season schedules ever since plans for the trip first began taking shape more than a year before. Timing our effort by calendar weeks and getting started on schedule had been a galling worry. Fifteen days later, I knew what Ken had meant Time was going to haunt me with each rising sun south of Nogales. We'd never be on schedule.

We refilled with gasoline at twenty four centavos a liter on the outskirts of Nogales and headed our car's white nose south toward Guaymas just as the Mexican siesta began for that 30th day of November, 1940.

We made fifty-four miles during the afternoon, after getting through Customs. And that night, sitting in our tiny little tent, backed against rocks and mesquite brush on a gravelly hill lop in northern Sonora, my typewriter m an upturned paper ease, and a very dim electric lantern hanging from a tent brace above my head, I began the daily chronicle of events which I hoped would take us through the long weeks ahead and all the weary miles to a dot of land at South America's Antarctic tip. If only I had known!

"Temperature stands about fifty degrees," I wrote, "And at this moment I can look out the tent flap and see Arnold and Ken over the camp Fire preparing a late meal of dried soup - and from the smell, burned potatoes it's damp and Chilly. But we're finally started. South."

From Nogales to Guaymas, is a well-graded, all-weather road of gravel. It's rough and full of washboard, but at least you can't get lost, for it's the only such road in the section.

We traveled casually and with determined care for the car. "Not a single unnecessary jolt must tax the springs or strain the body of this automobile," was our joint verdict.

"We've got too far to go: and too much load." We avoided every little hole; every rock the size of our fist, that lay in the road.

We splashed down the muddy main street of the town, stopped at a gas station, and while Arnold groomed the car with grease and water, Ken and I stocked the backend larder above the big extra gas tank, with canned beans, peas, corn and dried milk. We knew from here on there would be absolutely no eating or sleeping accommodations for tourists, except in one or two of the larger sea-coast towns. And these would be days apart. Of course this mattered little to us because we were prepared to stay wherever night found us.

We drove on south over jutting boulders, bad holes and curving coastline road to Empalme and there all semblance of graded or marked highway disappeared into the blue waters of the Pacific. It took us half an hour to find our way out of the little town. When we finally crossed the skinny railroad that headed down through the forest of mesquite and turned south with it in a two-rut trail that disappeared around the first bush, we knew we'd started the road-less stretches we'd been hearing about since the day we first began planning the expedition.

"What are we going to do when we come to a fork in the trail, no sign, and nobody around to ask?" I ventured, making it sound as casual as possible.

"Flip a coin," suggested Arnold. "Be about as accurate as trying to follow directions of the natives - unless your Spanish improves."

It had been raining. Puddles had filled the road all the way from Nogales. And now on this trail no car or vehicle had passed since muddy rain had filled the tracks. There was a desolate feeling about the mesquites; a loneliness about the thorny cactus. I felt as if we were heading into country no man knew. And the thought was disquieting. Whitaker drove.

I smile now when I think of that first hole. Following our dictum, Arnold had taken it easy on the car, afraid to hit the deep uneven ruts with speed for fear he'd break something. Besides there was a foot of water in the bottom. When the spinning rear wheels finally stopped, the nose of the car was barely started up the other side. Arnold got out gingerly his red face serious.

"Guess I should have power-dived," he said. "Well, let's get started."

We cut mesquite brush and tried to jam it under the rear wheels. We carried gravel from the railroad embankment in a water bucket, and poured on the brush. We gathered sticks, and pry poles. Finally we got down the block and tackle.

"Now we'll see how this thing works," I offered confidently, "It ought to bring us out."

Newspapers back in the States had called us "experienced explorers." Newspapers are sometimes inaccurate. Whitaker and I had ridden packhorses for eight days, once, out in southern Utah where Mormon pioneers had taken wagons across the sandstone gorges of the Colorado sixty years before. If that constituted "experienced exploration", then newspapers were right. But in planning this trip from Detroit to Cape Horn we had guessed at many things. This mud hole and the block and tackle was a case in point.

We hitched to a mesquite stump fifty feet ahead, and then Ken and I pulled with all our might. The back wheels spun. The car moved two inches-deeper in the mud. The front wheels had remained stationary. "Lesson number one," I said, wiping perspiration from my forehead. "Two men can't pull a three-ton car stuck in mud, with block and tackle."

Half an hour later, a small roadster with ten years of history and 7 Mexicans aboard, chugged up to the hole's edge and stopped. When the final Latin had slid out, or off, the car shook itself like a woolly dog, and died. Behind was a two wheeled packing-case trailer, bundled high. A family of Mexican fruit-pickers, we learned, returning from Southern California to Mazatlan.

And then began our real introduction to Latin Americanism.

Two more trucks came up to the place from the other way - there was a ranch nearby, we learned - before we got out. One of them did the actual work of hitching on and dragging us through. The roadster crossed a different way, as did one of the trucks, but nobody left the spot until all four cars were on safe ground again. In all the southern Republics we have yet to see a Latin American pass someone who might be in trouble without stopping to see if help is needed. The practice is as fundamental as a cross above their churches.

And after that first mud hole, we rapidly revised our "protection policy" for the car. Two days later Arnold came up to me, leaning his elbows on my open window. My hands were still on the wheel and the car stood dripping on the south end of a long mud hole we'd just dived through.

"How many lives've you got, Sullie?" His little moustache jerked with a quick grin. "Hope you brought along a few extra as spare parts, for if you go through many places like that you'll need them. Both wheels on the right side were clear of the water when you hit that last hump. I thought you were going over sure."

"So did I." My lips still hurt where I had bitten them.

But it was the only way to make progress. Time and again I dove into holes when I had no idea if the car could pull through. Time and again I turned on the windshield wiper before engaging gears that would send the car plunging into deep ruts of mud and water; for when we hit with speed, a sheet of mud and spray would engulf us. How we kept going in some of the holes we still don't know. Many of them stopped us. But the car took it. Bounding, bucking, plunging on two wheels. Once I slid completely sideways and dove into a fence. Another time the front wheels skidded and we locked with a giant cactus. The ax got us off that. (It was the first dent in the car! We sheared a half-inch shock absorber bolt clean. The extra heavy springs cracked down and rebounded like giant rubber.

"I don't know how one car can take it all," Arnold said grimly that night just out of Gusave. We were camped on the only spot we could find in the brush.

By this time we had begun to learn something about finding our way when there were no signs at trail forks. We asked every Mexican we passed. Their directions were always the same. Waving their arms around their heads three or four times, they'd stop with their fingers pointing straight up.

It was perfectly clear to them. And why should a gringo be so dumb as not to see it!

I can understand now why people had warned us about Latin American travel directions! But such people were wrong when they thought natives misdirected just to put us on the wrong road. It was simply our inability to understand them or the language. And I don't criticize myself too heavily for not deciphering the signs. Nobody could drive a car straight up. But as time went on, we did understand the language a bit better.

In the isolated sections of Mexico and Central America, travel is not between towns; it's out to some ranch or lumber cutting place, or fishing-dock. Towns live as independently of overland travel as if the rest of the world did not exist. How well we were to find that out before reaching San Jose, Costa Rica!

In Los Mochis, much-hidden town in the hundreds of miles of mesquite, organ-pipe cactus, and deepening tropic brush, we met our first Mexican who had been educated in the States. His English was like a pleasant dream suddenly recalled after long forgetting.

"I graduated from Berkley," he said evenly.

"How is the road below here?" We asked hopefully. "Surely, it should be better to Culiacan and Mazatlan." Those were the best towns on Mexico's west coast.

"What road, my friends?" he answered. "I'm afraid it's only a trail at best, and the rain was harder below here than where you've come. We had six days of it."

For a second none of us spoke. Arnold just lowered his head and rubber a sleeve across his eyes. Kenneth finally found my voice:

"That's all we've heard for days. It's pretty discouraging."

"I suppose. But you'll have a lot of it on this trip," I nodded.

Next day we struck a bit of wide-graded gravel leading into Las Bocas. The speedometer recorded twenty-five miles an hour! Such speed almost frightened us. We ferried Rio Fuerte on a primitive raft made of planks laid across two flat-bottomed row-boats.

Friday night, December 6, 1940, we camped on a rocky beach of Rio Culiacan, right outside the town. It was seven days since we entered Mexico. We'd come six hundred miles, with eleven hundred still to go to reach the Capital. We were tired. Inside.

"Shall we give up and ship from hereto Guadalajara?" I asked the boys as we stopped half a mile out of Culiacan. We had just come charging in low gear through a full quarter mile of deep ruts, which landed us at the foot of a tropic-brush covered hill. The boys had jumped out the moving car as help to the failing motor when they saw how deep and sticky the ruts were. The "help"had been exactly enough. I backed up in to a niche in the brush where I could turn around, and waited for them. Perhaps I was more than a little depressed, for we hadn't seen the sun in three days. It was streaming hot and threatened more rain constantly. The conference was a sober one.

"Once we take the car's wheels off the ground," argued Whitaker, "we're done so far as the story of the expedition is concerned."

"I agree," echoed Van Hee.

"But from here to Mexico City doesn't count. Anyone can drive to Mexico City - On pavement. We should have done it, too."

"But the point is, Sullie-";

"Yes, and I'd like to see the kind of road Mexicans say can't be traveled," Ken put in. "Seems to me they wallow through mud with less worry than anybody I've ever seen. This spot must be a honey."

"Let's push on till we reach the Laguna (Bog)," Arnold voted. "At least one truck got that far. We're certain of that."

"Hope there'll always be two of us say to keep going." I was relieved for the moment at their confidence. "If there is, we'll make Cape Horn." We drove on.

Local people were hired to help build trails so the expedition could continue.

From the hill we followed two twisting wheel tracks - once in them we couldn't get out - scarping trees and brush, dropping into occasional little gullies and climbing up again. But mostly the way was level and full of mud.

The drying clay left us almost helpless. Only high-wheeled trucks passed that way. The tracks were single ruts, eight to twelve inches deep. In the bottom was slick mud, tops and edges were dried crusts. We had two inches extra clearance due to bigger wheels, but low shock absorbers gouged the mountainous clods, the rear axle dragged in the middle, and the wheels spun in the bottoms. We dove, pitched, and raced, bruising the tires against rut sides in an effort to get traction we could not find in the bottom. The fabric-and-rubber sidewalk took steady punishment. Patches tore from the walls and little chunks from the outside tread. Every bend we rounded we expected to see the laguna lying before us.

Goodyear supplied the expedition with twelve specially made 18-inch tires; they did not get a single flat.

It must have been two-thirty when we hit the first real bog we thought might be the beginnings of the laguna. A truck driver had built a brush road out to one side for some forty yards, then hugged the roadside for another hundred. We started, but our heavy load went right through the brush.

"I was afraid of that." We squinted out the windshield. "That truck was a light one. I've been watching the tracks to see, but I wasn't sure until now."

We climbed out and began work. First we unloaded. Gradually we backed onto some sand with the empty car, then while Arnold put on chains and added more brush to the road, Ken and I carried our half ton of equipment that hundred and forty yards through the mud. The atmosphere was heavy.

Grey daylight seemed something we must push our way through. Temperature was near a hundred. There wasn't a dry thread in our clothes when we finished. It was hard to breathe.

"Ready?" I asked Arnold.

"Ready."

I got in started the motor and pushed the accelerator almost to the floor. The car lunged like a floundering horse, but at last stood on solid ground near the luggage. We loaded up without a word.

Next place we thought was the laguna became another quarter mile of deep ruts. The crust was dry again; the bottoms slick. Our hands were full of thorns when we finally had dry sticks and green brush laid end to end in the bottom of the tracks. And it was four o'clock.

"Shall we try it with the load?"

I had been doing all the driving those few days. It was a foolish idea, I admit, for Arnold can take a car through hard places easier - at least on the car - than anyone I know. And finally, in southern Mexico and Central America when going became really difficult, my bearings straightened out and he did most of the driving. But now, if something had to happen to the car, I felt I'd rather be driving when the break came. Then I should be to blame.

"I think she'll take it, Sullie. That brush will give traction and some lift. Then you have the chains-"

We often wished that car might have been alive. Something like a gallant horse, so when we reached the other side of a bad stretch we could have patted its shoulders, rubbed its neck, and whispered appreciation into its ears. There were times when it performed as if it were alive. And the bogs south of Culiacan were instances in point.

We looked at the speedometer. We had come thirty miles from Culiacan over road every Mexican had said we'd never get through. And the truck the night before had not reached Quila, so we knew we'd soon see where it turned around and went back. We did.

The Plymouth barely fits through the bull-cart trails.

Down from the railroad track about half a mile, it was. Stopping the car well back on solid ground, so we could turn around if we had to, I walked on up to the water. It was probably a hundred and fifty yards across, and there was no way of telling by appearance how deep or boggy it was. The truck tracks reached the edge, backed around and started in return direction. I motioned Arnold to bring the car ahead. By the time he reached there, I had my shoes and socks off.

"We'll tell your wife where we last saw you," shouted Ken as I began wading. "And we'll yell if it goes over your head."

Across, through a track I thought one wheel would follow, and back, where the other would then roll. Water came up to my knees. I had an idea.

"Boggy?" Arnold wanted to know.

"Enough. But not as bad as I think that truck driver though it was. I believe she'll go through empty."

"And carry this stuff across on our backs?" It was Ken.

"We've got the rubber boat," Arnold laughed.

"Well, I'd rather be stuck here where there's a spot in the brush wide enough to set up our beds than to try going back. We'd never make it."

"We're with you."

When the car was unloaded, I backed up. Arnold had disconnected the fan belt to avoid splashing water over the spark plugs and distributor.

"Don't hit it too hard at the start," he cautioned. "But if it begins to die, slide the clutch and give'er hell."

I can still feel my lower lip between my teeth. I kept the motor roaring all the while, sliding the clutch in and out, maintaining all the speed and power I dared without stalling completely against a wall of deep water. The chains clanked and churned. Water slopped up underneath the floorboards and waves of it rolled to each side. But we pulled through, I thought with power to spare.

On the other side I climbed out and shouted back: "I believe she'll make it with part of the luggage. Shall I try?"

"Suit you," Arnold called. "But if you stall in there now after getting safely through once, we'll -" I backed into the brush and turned around.

Five trips the car made through that "laguna" that night, before the luggage was all on the Quila side. We thought from there on we'd have easy sailing into steeple-towered Quila. We were disappointed. Three hundred yards on was another bog. We reconnoitered with flashlights. Stationing Ken and Arnold at spots in the darkness where the bogs were worse, I again pushed the accelerator to the floorboards, car in low gear.

"Absolutely beautiful," Arnold said as he settled again in the seat. "This car can take it."

"It rocked a bit though," I admitted. "I could feel it."

A crowd of Mexicans gathered about us as we pulled to a stop in front of a squat broken-walled place with the word "Hotel" hanging from a creaking brace.

There was a river outside Quila to cross: river with four folks, to be forded only with the help of mules and a high-wheeled cart to carry our equipment over so it would not get wet. There was even worse road from Quila south to Mazatlan than we had traversed in reaching Quila from the north. There were still the many miles of brush and lowland mud below Mazatlan until we turned eastward into the mountains at Santiago for the steep climb to Tepic. And finally there were the unpredictable miles of rocky trail across the Barrancas to Tequila and Guadalajara. From there we would have pavement to Mexico City. Pavement! Was there such a thing in the world?

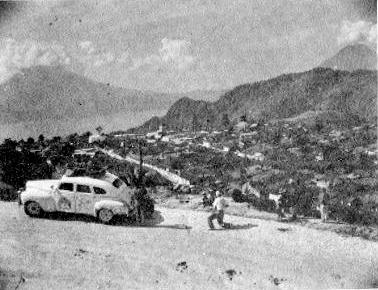

On the shores of Lake Managua, Nicaragua.

Over looking Solola, Guatemala on Lake Atitlan. San Pedro Volcano and Toliman Volcano in the background.

We got across the four-forked river all right-though water backed up under the door handles on the upper side of the car in doing it. And when we opened the doors on the south bank, water poured out as from a submerged box just brought to the surface of a lake. We even got through the mud-most of it-toward Mazatlan.

We made fourteen miles that first day out of Quila. Prophecies regarding impossibilities of the road were all accurate, except the one that we simply couldn't get through. Two stretches almost fulfilled even that. Cutting brush and stumps alongside a laguna, we literally chopped out our own road. Again it was hot. Hard to breathe. Maybe we were working too fast. Anyhow, we were unaccustomed to such heat.

A unique roadway under a small waterfall.

As we reached a fork in the jungle lane, a single piece of board dangled from a broken wire on a telephone post. "Mazatlan"it said, but the arrow pointed straight at the ground.

"You guess," announced Arnold, standing with his face pointed up at the broken board.

"The telephone line goes that way," Ken observed.

"And telephone lines go somewhere, even in Mexico." It was my guess. "Let's find out." We headed right.

That night we camped on the dry rocky bank of a river outside a grass-hutted clump called Obispo. The Alcalde in Quila had said we'd never reach there: that the stretches of jungle mud to that point were the worst on Mexico's west coast. But we were there.

"Well, I don't know," I announced dismally. "If the road is any worse ahead, as they say it is, I don't know!" It was a bad sign.

Sullivan purchases bananas from the United Fruit Compnay for 24 American cents.

Next morning it was I who wanted to go on. Not because I was optimistic about the road ahead. But that back of us was a nightmare. And besides, even if we arrived again at Quila to ship on the railroad, the agent had said no one could ride with the automobile. That was unthinkable: all our cameras and equipment in an unguarded car, we went on.

Local townspeople and politicians gather around the

Plymouth for photos.

Twice that day we got stuck in mud. It seemed a concoction of heavy glue, cold tar, chocolate clay and water. Mountains of it stuck to the wheels until they could not even turn through the fender wells without scraping. We couldn't shovel it. It stuck to the spade in great single wads. If we tried to push it off with our boots it was like anchoring our feet in lead. Our shoulders ached trying to shake it from the shovel. Our spirits were very low that day. Almost too low.

And it was while we were still struggling in that one bog, buried to the hubs in sticky mud, we heard the sound of another motor. I straightened slowly from the heavy shovel. Could it be true, or was the silence of mud and jungle getting me down! In five minutes two cars came up in ahead of us, breaking the trail from their way as we had been doing from ours. That moment of relief is not easily described.

It had been so long since we'd seen a car track ahead of us: any kind of wheel track for that matter. Our eyes blurred from looking down each stretch of jungle lane into which we turned, seeing nothing but mounds of mud, without a fresh imprint of any kind in it. Gradually we had come to think there were no other living things, or wheels, in the whole world: only mud, incredible, mucilaginous mud. And through it all we had to take a big white Plymouth, loaded twice as heavily as a car should be.

It took us five days to go from Mazatlan to Mexico City. We encountered the same difficulties as in the days before; first, mud, deep ruts, weed-and-stump-filled pastures, and torturous days and nights of heats, gnats and mosquitoes. Second, the three to ten-mile-an-hour progress through the mountains up from Santiago to Tepic, to the Barrancas and on to the pavement at Tequila. Hours dragged but days seemed to race by without our getting anywhere before night fell. The little mountain hamlets along that road were almost as hard to get through as the deep mud and bogs of the lowlands. We'd never seen such steep grades, such outcroppings of rocks, such ditches and holes right in the center of towns. And boulders made some of the streets almost impassable. Several times we backed down to get a fresh start at particularly bad hills while curious or laughing natives lined doorways of huts on both sides of the steep "avenidas." We low-geared through more main streets in Mexico, than the rest of the America's combined.

The Barrancas - a great V-shaped valley cut with numberless finger canyons running down out of the high mountains to join finally in one great gorge at the bottom were not half so bad as advance publicity had described them. It was well we were going south instead of north however. Coming down that mountainside I put the car in low gear applied the emergency and foot brakes all at the same time, and still had to use extreme caution on the curves. Our brakes smoked and burned. We've seen steep countryside, but the north side of the Barrancas still holds something of a record for grade. We wondered if we'd ever get up the other side. It wasn't so difficult as the downgrade though, and we had almost no trouble climbing it.

What relief we felt in driving onto the pavement at Tequila, a few miles out of Guadalajara!

In Guadalajara we sat down to a huge steak dinner. It seemed as if we had already reached Cape Horn and this, our victory dinner.

We left Guadalajara at 7:30 p.m. that same night, Saturday, December 14 and drove until 1:00 a.m., setting up our beds in the brush alongside Lago Patzucaro. By 1:10 a.m. we were sound asleep with peaceful visions of the Mexican Capital, warm shower baths, and crisp sheets, filling our dreams.

We arrived in the city next afternoon at 3:30. Fifteen days out of Nogales. We had expected to do the trip in eight.

We were anxious to start south, for in spite of another feeling time wouldn't count after we began the Oaxaca stretch, we still had to get through Central America before the rains, and to Cape Horn before South America's winter set in. We began deciding which day we could leave. It looked as if Wednesday, December 25th, would be it. Christmas.

There was little time those days in the Mexican Capital to worry about the trail below Oaxaca. We were certain it was bad. How bad, there was no way of telling. Survey work for the Pan American Highway was being carried on through the mountains, and each camp had been notified of our coming and of Mexico's wish to help us over the trail. Those camps could be reached only by horses. Pack burros brought in supplies.

"Surely we can negotiate the stretch in ten days to two weeks," I argued. "It's only about fifty miles. And it is a trail." (How foolish that argument sounds now!)

"I met an American chap today who had just come over it on foot,"" Arnold replied grimly. "He said he didn't see how in the world a car could get through. He had to jump from one boulder to another. It took him three days."

"Would it do any good to go in on horseback first?" Ken wanted to know. "If it's too bad we can come back to Puebla and try the trail on the east side of the mountains that Mr. James recommended." (He referred to E. W. James, Chief of Public Transport, Division of Public Roads, Washington). Mr. James had marked a map of both North and South America for us: given us four pages of recommendations. He had told us of the Oaxaca stretch, and said he had no Idea we could successfully cross it: that if we wanted to try the entire distance of Mexico, he'd recommend the lowlands near the railroad line on the eastern slopes, then back across the Isthmus to Jucitan and Tehuantepec. We had seriously considered trying it, until the men in Hernandez' office simply shook their heads "Swamps," they said. I answered Ken's question.

"We'd lose at least six days if we tried to reconnoiter. To do any good we'd have to cover the entire distance because the last part of the trail might be worse than the first part, and we'd never know till we got there. We may as well start with the car, and do what has to he done to get through."

"I agree" Arnold added. We changed the subject. None of us like to admit how worried we were.

There was another important thing to do in Mexico City. After two thousand miles of West Coast mud, we knew we were carrying too much baggage. What to leave, and where, troubled us.

"You can store anything here in the Embassy you want if it isn't too big," John Carrigan told us "Maybe it'll be here when you get back if you do." He laughed, and so did we. We went hack to Shirley Courts to sort out the stuff.

Fourteen hundred pounds of equipment: TWICE TO MUCH, AND WE COULDN’T SEE A THING TO LEAVE! We went through every bag, box and roll, estimating weight and necessity. Cameras, film, tripods, and special photographic equipment: two hundred fifty pounds-absolute necessities. Three bedrolls with air mattresses; seventy-five pounds: necessity, for complete rest was essential to health and that was the important thing in the expedition.

Bed cuts, forty-five pounds: not absolutely necessary, but nearly so. They would keep us off the ground, out of dampness, snakes, crawlers, etc. We took the cots. Rubber boat? Forty-five pounds. We argued about that Our stuff could be loaded into high-wheel carts, we'd found, when we crossed rivers so deep the water would float inside. But what if we had to cross rivers where there were no carts? The discussion was long. We took the boat.

So it was with every item. Ropes, heavy pulleys, block and tackle, tools (part of them were left), gasoline stove, cooking equipment and food, clothing and personal effects, typewriter, paper, etc. We finally left about two hundred pounds: all heavy clothing-since we expected to be out of Argentina before winter set in! - One suit each - a forty-five pound tarpaulin, shotgun and sixty pounds of shells. We left Mexico City about 2 p.m. It was Christmas Day.

We climbed rocky dug ways. washed and corroded with rains We jolted over boulders and twisting trails. We hanged across two-foot ditches that almost shook the motor from under the hood. We cut around sharp blind bends with crumbling edges under our wheels. And once Kenneth screamed at me.

"Good lord. Sullie! Move, you fool!" He was sitting on the outside, and jerked at the door handle as if he were going to lump from the car, I had stopped momentarily in the middle of a bend, trying to be sure I wouldn't scrape the left front fender against the inside wall. I eased ahead, letting the clutch gradually into) the still racing motor. Arnold joined in the raving reproach.

"If you're going to drive, look where you do it!"

"And where you stop!" Ken wax vehement. "Your right rear wheel actually rut the crumbling edge of that curve and you stopped right over a washout. The ground was giving way when I yelled." It was a long drop-off over that side.

I answered them quietly, "The left front fender was scraping the wall over there. That curve was simply too short."

It wasn't much defense. They grunted. We drove on.

From there on the road zigzagged up and down the very crests of pine covered ridges and mountains: the premier skyline drive of the trip.

Then came the worst dug way of all. Four times we tried to get up. Four times we backed carefully down for a new try. The twisting ascent was cut with diagonal ditches washed to the outside, and there was barely a foot of room from the wheel tracks to the fall-off. It was not pleasant work.

On the fifth try Arnold backed well down on the ridge below, forgot the foot of room and the diagonal ditches, forgot the loose rock and the fall-off. He came back with all the speed and power he could pour into the roaring motor. It was a spectacular moment: flying dust, driving gravel, lunging car as it cleared the ditches, but at the end it rested at the top of the grade. We stood for a moment looking back down the trail, then over the side. We shook hands, climbed in and drove on.

In three days we reached Oaxaca.

It was too late to hunt up the Chief Engineer of Roads the day we arrived. Besides we wanted to get up on the mountaintop nearby, where lay the ancient ruined temples of Monte Alban. We hoped officials would let us camp at the ruin during our stay in Oaxaca.

We drove into the great amphitheater footing the wide 135-foot stairs at the north end of the pre-historic city, showed our papers and letters to the guard, got his smiling, "Seguramente, Senores! Seguramente!" and that night we slept in the stone cradles of the dead. The ghosts of ancient men, who with unbelievable hands built Monte Alban from fitted stone and mortar high above the jeweled city of Oaxaca, looked down that evening on a big white Plymouth camped in their huge arena.

All forenoon, on December 31, I sat with one leg hanging over a ledge of Mitla ruins, pounding my typewriter. The shade moved with the sun. I moved with the shade.

Arnold and Ken had gone back to Oaxaca, twenty-nine miles away, to buy more food, a large water can we could lash to the front bumper, another pick, an accessory canteen, and to bring Evereto our guide. When they returned we would be ready to go.

We left Mitla by one o'clock. It was New Year's Eve day. And as on Christmas none of us spoke. We flipped a coin. I lost, then climbed on the right front fender so Evereto could sit inside with the driver to show the way. We three would alternate positions as the hours passed.

It was after dark when we pulled to the side of the road near the opening of an abandoned mine, below a mountain crest called Cerro Colorado. That would be a suitable place, we thought, to spend New Year's Eve. Quiet. Clean. And nicely sheltered. We could yell, shoot off firecrackers, sing, toot horns, throw confetti; anything we wanted. We would bother no one. We settled on a program of hurrying through supper, and preparing for bed. Ken and Arnold each finally took a flashlight and started down the old incline to explore the empty mine.

"Go to bed this early on New Year's Eve? Not while we're young and romantic. Last year it was four o'clock before we went to bed."

"Beat it," I said.

They disappeared into the tunnel mouth that even in the night was a black spot in the mountainside. I sat in the car, pounding my typewriter again.

"While you people in the States are tooting the Old Year out and the New Year in," said the first line, "we're sitting here in the car on a box of film, near an old mine, high in the tops of Mexico's southern mountains. It's so quiet we can hear the ringing silence. Hope you're having fun-"

New Year's Day was wonderful. We traveled three and two-tenths miles. Shortly after leaving the mine opening, we saw where all traffic left the graded road and dropped down into the canyon on our right. Evereto shook one finger back and forth in front of his face and pointed straight ahead. "Directo, directo," he said vigorously, then jerked his head toward the canyon. "San Jose over there."

"Can't be long now," Arnold grunted. Ken was riding the front tender at the time. I explained Arnold's comment to Evereto in Spanish.

"One mile more. Then we turn off on the trail," was his answer.

The tough stretch we'd worried so much about was at last upon us and it was New Year's Day!

Sullivan Richardson Points to the halfway point on the

car door map.

We moved on up the climbing road cut. Dimmer and dimmer became the tracks of previous wheels: wheels of road equipment that had passed along before us. Now there began to appear boulders and rocks that had slipped from the mountain walls of the cut, and had been left to lie in the roadbed. The hamlet of San Jose slipped by us, far below on the right, and we knew we were ahead and south of the point where all wheel traffic turns back toward Mitla and Oaxaca. Beyond a turn of the mountain Evereto shook his finger again, and we pulled to a stop. A dim foot trail for burros and human feet slid off the rock-choked roadbed, and began a sloping descent along the brush-covered mountainside. Evereto stood for a moment looking all around, then motioned ahead down the trail.

Under military escort, the expedition drives past the Panama Canal.

"This is it," Ken said. "Whoopee!" But it was a very weak whoop.

That beginning hundred yards was memorable. First, because it was the start of an "impossible" fifty miles. And second, it plunged us into work that drove all thoughts of "leaving civilization" completely from our minds. From the roadbed cut above, a small landslide of rock and brush had slipped down the mountainside and engulfed the trail. The burro path picked its way through the slide, but before the car could get through we'd have to move a lot of rock. We got out the picks, shovels and hoe. I took pictures for a few minutes, and then joined the others in work.

All through those fifty miles of mountains a trail had been cut, years before: a trail wide enough for a cart. But carts never traveled it. The grades were much to steep for anything on wheels, and the road was never finished. Rains and burros soon cut it to pieces. Boulders, gullies, caved-in embankments, and washed-out holes reduced it to the barest kind of footpath. But the foundation of a trail, wide enough for a car, was there. All we had to do was find it, then try to get over it.

In two hours we had cleaned the slide enough, we thought, to let us by. As a safety factor we had dug a trench on the upper side, deep enough to keep the left wheels in and hold the car from sliding over the slanting side to the right. Whitaker started for the car.

"Easy," I cautioned him, "and don't get out of that trench."

He took one last look at the cleared trail, the upper trench, and one quick look over the side. He rubbed his hand over his beard and eyes, and then got in the car. From then on he looked straight ahead on the trail, and at my motioning fingers held high above my head.

Even with my guidance he crowded the up side of the trench and almost forced the wheels out of it, trying to stay away from the drop-off.

I shouted at him, "Stay down! Stay down! And follow my fingers," the car moved slowly over the rocks. Evereto leaned on a shovel back of me, chewing.

Ken was on the trail behind him, operating my movie camera on a tripod. I had a still camera handy in case anything went wrong. Not that I expected it to.

But the three of us had made an agreement before leaving Detroit that if tragedy ever struck, and one man was free and in a position where he could do nothing to help, he was to take pictures-if he had a camera. And in this spot, if the car went over the side, no one could help anybody.

"Glad that's done," Arnold said when the car stood safely on level ground once more. He slid slowly from the front seat and mopped his head again with his hand. We didn't ask if he were nervous. And he made no further comment. We talked about the road ahead.

From then on, Evereto, Ken and I walked. We lifted boulders out of the road, and we lifted them back in. When protruding rocks were too jagged and high for the car's clearance, and we couldn't dig them out, we built more rock around them, making a regular pile which would raise the wheels high enough to clear frame, oil pan and rear axle housing, of danger. It was toil.

Hour after hour we crept along that trail, mostly down hill. The burro-trail turns were difficult. Several times the outside front wheel would be completely off the side, moving forward two, three or four inches at a time on makeshift foundations which we built up under it with loose rock. Time after time we were on our knees or stomachs, trying to arrange more loose rock under the wheels, to lift them a half inch higher, for more clearance above a point of rock that threatened to jab a hole in the oil pan.

We dropped into gullies, and charged up sides in quick jolting runs, attempting to gather momentum for help in the last steep yards of the climb.

Sometimes we made it without a stop. Other times we blocked the wheels to get new power and push. Finally, about four o'clock we saw the Tehuantepec River below us. It was great relief. Soon we'd be down alongside the stream where we could camp, swim, and relax. Or so we thought.

In the last quarter mile the trail suddenly dropped into another gully, turned right, then climbed out again up the steepest hill we'd seen yet. Half way up was a sharp bend and in the center of it a boulder, almost three feet across. How far it went into the ground we didn't know. It seemed anchored in cement. Rains had washed around it, leaving it too high to straddle and too straight up to climb over. We began throwing loose rock around it.

Four times that afternoon we tried to negotiate the bend. Already we had scraped the car doors, dented the fenders, jammed and jerked the frame, so we were past the point of caution for car punishment. We drove into that boulder with all the speed we could gather, and when the front wheel hit the loose rock, it banged against the buried shoulder like a sharp high curb, and stopped.

We unloaded and tried three times more. Then we began slipping the clutch, blocking the rear wheels, and trying to inch up. From a standstill position against the boulder we jerked the car forward by letting the clutch into the roaring motor with a sudden plunge. It was punishment on the entire drive system, but we felt it had to be done.

The motor got so hot we couldn't turn it off. The ignition key was dead, but the heat of the engine ignited the gas and kept the thing running. Stench of the burning clutch filled the air. And then in one last violent jerk-the front wheels were finally over the boulder-the right rear one went over the side with a crumbling of the washed-out shoulder beneath. The drop was almost perpendicular, for some twenty feet. That stopped us.

"I go to Nejapa, for bulls to pull car tomorrow morning," Evereto offered when we finally translated his Spanish. "Not very far. Be back 7:30 morning, early."

We held conference. Two horsemen came along and tried to get by the stalled car on the dug way. They finally dismounted, and led their wheezy mounts through the squeeze between the ragged rock wall and the white car doors. The horses had never seen an automobile apparently, and as they lunged through the last four feet we hardly noticed the stirrups and saddle gear as they banged and scraped against the doors and fenders.

"Bad business," Arnold grunted.

"Be worse than that before we get through these mountains," I prophesied. "Shall we send Evereto along with them?"

"Might as well," voted Ken. Evereto went.

That night we set up our beds on the crest of the little hill fifty feet ahead of the car. On our right, just over the side of the dug way, the mountainside dropped madly down to the river some five hundred feet below.

"Tonight is New Year's Night," I began in my notes, after Arnold and Ken were deep inside their sleeping bags. "I'm suing here straddled out in an empty car, which slants at some thirty degrees over the side of a dug way high above the Tehuantepec river. I can hardly find a comfortable way to sit and type. How long we'll be stuck here isn't worth a guess. But if the car slips another six inches sideways, you can start thinking of nice things to say over final remains of the expedition!"

Spindle-legged grasshopper of a man, this Ruperto Reis, who came back with Evereto next morning- at ten o'clock instead of 7:30. They brought a pair of yoked bulls, to pull us up the hill and also through the deep river below-when, and if, we got down to it.

Christening the car "Miss Pan-America" with water from the Panama Canal.

Dr. Zapata, third from left, welcomes the expedition to Buenaventura, Colombia.

"Those bulls will never pull that car!" we snorted at him when he commanded us not to start the motor for fear of frightening them.

They jerked, slammed sideways, tore up dust and made a commotion generally, but the car still sat where we had left it, except that the constant jerking seemed to make it settle even farther over the side. That frankly worried us.

Finally I took charge of the expedition again, and told Ruperto to watch the bulls and try to make them pull with the motor. After the first blast from the exhaust they seemed to settle down a bit, and with our pushing, and one fortunate pull from them which came at the exact moment the power of the motor went into the rear wheels, we at last got the empty car on top that hill.

While we waited that morning, we had carried all the equipment down to the water's edge, knowing we'd have to unload to cross the stream anyhow.

Now it was only a matter of caution getting the car down, too. The trail dropped so fast it seemed the car would slide with all wheels locked, and we didn't breathe freely until it was finally sitting out in the sun near the luggage on the rocky bed of the river. We knew now, if not before, there was no turning back. We'd never in the world get up the mountain we had just come down. What lay ahead we didn't know. What lay behind was a nightmare-even coming down. And going back would be a physical impossibility, we thought. We only prayed that the "going up" places ahead would never be like this.

Seven times that day we crossed the Tehuantepec River. Twice the equipment was carried across on our shoulders because the water was so deep we were afraid it would run in the car and wet everything. The first crossing, there at the foot of that morning dug way, was one of these. Right near the sandy bank the drop-off into the water was quite deep. Arnold had taken off the fan belt, to avoid throwing water over the motor. Then he swathed the spark plugs in dry towels, and put a three-feet extension on the exhaust pipe, bringing the opening high up above where water would come.

With the car empty he dropped off into that stream. In that first drop-off the water came up almost to the top of the radiator, but swallowed, and the car plunged on through. Our shouts rose above the rocky turrets of the narrows. Ruperto shook his seven-hair moustache in amazement and shouted, too.

We didn't need his bulls.

But as the day wore on, and we crossed and re-crossed the river, getting down toward the little hamlet of Nejapa, we had our troubles. Time and again we moved boulders to clear a path for the car. Anything so we could get through. Rocks the size of a man's head, and even larger, we paid no attention to.

They wouldn't rip a hole in the oil pan or drive a point up into the gas tank. Both these vital spots of the car, were protected by extra plates of steel, but even so, we were afraid for them.

As three o'clock approached and we had still only made two miles, we began to realize more than ever how unaccustomed we were to hard physical labor. Our hands were cracking with the dust and gravelly dirt, the ends of our fingers were sore, and our backs and shoulders ached from straining at the heavy boulders. We were discouraged and weary with our slow progress. Finally we made a mistake in choosing a spot to cross the river. There was bad sand in the bottom.

Before the car was on dry land again we had a great crowd of natives standing, sitting, or walking around all over the place. They had gathered from Nejapa four miles away: from the little farms that now choked the narrow valley. An automobile coming to Nejapa was the event of a lifetime. Some of the people were frightened by it and stood a long way off, apparently expecting it to explode any moment. Others stood so close we kept bumping into them in our efforts to rescue the car. Ruperto was in his glory. He was a magnificent General. Yes, he worked himself, ceaselessly. But he shouted orders to the bystanders pressing some of them into service, demanding others to stand back and give us room, until we wanted to stand back ourselves and watch him.

The following days proved both exciting and exhausting. Arriving next morning, after our river-crossing camp, at Nejapa we were welcomed with great enthusiasm by the populace of the little village. There were no wheels of any kind in the town. Just burros, horses, and black-sandaled human feet.

As we left Nejapa, all the children of the village fell in behind the big white car, racing along shrieking at the tops of their voices. What a day of celebration, to have an automobile come to their city!

The following days things happened rapidly. First day out of Nejapa we made three miles. That was Friday. Saturday, we made four-tenths of a mile and ended the day about two o'clock in the afternoon stuck on a mountainside with bulls that wouldn't pull with the car, and a clutch completely burned out.

On Sunday Arnold changed the clutch. We had a spare plate in the reserves. From now on there could be no more slipping of the clutch, for when this one went there was not another, that size, this side of Detroit. We'd have to pull with block and tackle instead.

Came Monday morning, and more men. They were a motley bunch of Indians, talking native jargon between themselves and a badly garbled Spanish to us. In the days that followed we learned to like them all immensely, except one or two who proved so lazy we sent them home and got others to fill their places. Monday we made 1:6 miles; Tuesday, 1:7; Wednesday, 1:5; Thursday, 1:3; Friday. 0:7; and Saturday it took us a full day to go twenty-five yards.

What a week!

Again and again we had the men carry the luggage on their backs up the rocky trail, then hitching onto the car with a straight rope from the bumper, we'd give the "sta bueno!" sign, and begin chanting and yelling, "Arriba! Arriba! Heckle! Heckle!" And those motley sons of southern Mexico, leather-faced, tattered, broken-sandaled, would begin to yell and pull like wild men. When the pull was over and the car stood atop the bad stretch, they dropped to the ground in a panting pile of human begins, laughing and shouting with unrestrained glee.

In nine days we traveled twelve miles. What it cost the car in paint, dents, body pounding and punishment to the drive system, we dared not guess. The two rear fenders began to look like wrinkled tortillas and were starting to pull loose from the car body. Both doors on the right side were caved in, with an ugly gouged-in scratch across the center. They'd both still open, however. The glass of two windows was broken. But the motor still roared when we stepped on the accelerator. That was the great comfort. The car was a Trojan.

It was a day later we hit the big boulder. Rolling down from the mountainside it had completely blocked the trail. Burros could get by, yes, but a car was out of the question. For an hour we tried to decide what to do. To move the rock was impossible. It was larger than the car. We had no power tools, no dynamite, nothing but a couple of big hammers, some bars, picks and shovels. To build a makeshift road around was likewise impossible. On the upside the mountain rose steeply for several hundred yards. On the downside it dropped dizzily from the edge of the trail.

"We've got to break that boulder some way," I said. "There is no other choice."

"But how can you break a rock like that without powder?" demanded Ken. "It's like granite."

"Well, we can't pray it off the trail!" Arnold was snapping. "And wishing won't work either. Let's get after it."

"Then take the men and go on ahead," I suggested. "Work the trail as far as you can. I used to break boulders in the copper mines in Arizona, and while I don't relish the job, I can probably do more with a hammer than either of you. Come back at 5:30 for camp, and we'll see how I've made out."

The rest of the afternoon I worked. When they returned I had chipped exactly fourteen inches off the boulder's waist. We measured with the hoe handle from the rock to the crumbling soft dirt at the trail's edge. Then we measured the exact width of the car from the edge of the body to the outside of the right rear tire.

"Six inches more off the rock would give us two inches dirt on the outside of the trail," I observed.

"And do you want to sit in the car and drive it by there with only two inches of soft dirt between you and that canyon?" Ken wanted to know.

"Can't," Arnold put in, "even if we absolutely scraped the boulder. We'd need a foot of room on the edge of this trail. Even then it might crumble under the weight of the car and driving power in the wheels."

"We'll never get sixteen inches more off that rock," I retorted. "If we had the hammers that pound the gong of doom, we wouldn’t! That boulder's hard."

Until it was so dark we could no longer see, we kept driving at the rock's stubborn flintiness with the sledges. Those first fourteen inches had been easy in comparison. It was toil now. That night we held a solemn council.

"We aren't by this boulder yet," Ken observed, making a funny face. "Hope you 'aint overlooking' that incidental item." It was good that one of the three of us usually found a way to inject a bit of humor into the situation whenever problems began weighing too heavily. But Ken's humor at that moment was passed by.

"I believe we can hook the block and tackle onto the back end of the car, to secure it just in case, then get all the men but two, onto the front rope and drag it by that boulder without putting any driving power in the rear wheels. Those two men and I can stay at the back and feed slack to the block and tackle. That'll let the car roll free and I believe two inches of dirt outside the wheel will be sufficient."

"Maybe," Arnold said.

"Well, with the block and tackle hitched on, there would be no actual danger of losing the car."

"Could three men hold that automobile, with block and tackle??"

"Of course, as long as it didn't start rolling in the first place."

We fell silent again. The flames of the fire crackled under a knotty log we'd put on a little while before. Evereto got up, shook himself, pulled his thin blanket from the car and lay down with his head against the rear wheel. We still sat.

"Know how long we've been in this stretch already?" Arnold broke the silence.

"Fourteen days," I answered, not raising my head. I was staring at the fire, "And we thought we could be through in that time."

"Something's going bad in the transmission, too," continued Arnold, as if he'd been afraid to announce the bad news before. "I'm scared stiff to think of what it might be."

"Teeth?"

"Don't know. But I sure don't like that clicking."

That night, by the big boulder-south of San Juan Garcia, was one of the solemn nights of the expedition.

At 7:30 next morning we were working again. By nine o'clock we thought we had our two inches "spare dirt" on the outside edge of the drop-off. Then came the job of getting the car by.

Everything started according to plan. The block and tackle was anchored to a tree up on the mountain side above us, then fastened to the outside rear spring shackle of the car. Arnold had driven the machine up to where the front wheels stood even with the boulder, and by sighting along the outside, we could tell we had about the two inches we were after-and no more! The men were holding the long rope from the front bumper, waiting for the "go-ahead." Ken was to work with them, and at the same time guide Arnold with movements of his fingers held above his head. I was to be anchorman on the block and tackle, with two other men to help me in case either end of the car went over. Everything was ready. Arnold rubbed his long-bearded chin and stepped again into the car. He didn't look off over the side. Only ahead, at Ken.

"If anything slips, we'll yell for Gabriel to start tooting." It was an effort to be funny. It went flat. And this was one place no cameras were set up for action. "Shoot!" I yelled to Ken and to the men ahead. They bent into the pull and the car started forward.

"No! No" I heard Ken shout suddenly. I was behind the car and could not see what going on. Then I heard the scraping sound of rock against metal. Arnold was crowding the boulder too closely. Who could blame him? The front half of the car was by. At the moment everything had stopped and the car rested there, motionless. The ropes of the block and tackle were limp and slack. We were having difficulty getting the strands through fast enough to let the car roll freely.

Suddenly Ken appeared, half up the side of the boulder, like a scared rabbit. He was yelling at me.

"For Lord's Sake, Sullie! Tighten that rope, you fool' Quick!"

"Go back to the men and leave me alone!" I answered, "I know what I'm doing. Make those fellows pull and hurry!"

"But keep the rope tight, or we'll lose the car!"

"Shut up, and have the men pull!" I lifted my voice up over the car. At that second I thought I could see it slide a little to the outside. "Hombres! Heckle! Heckle Abora! Heckle!"

I've admitted before my Spanish was bad. And Heckle I'm sure, means nothing, grammatically. But these gaunt, leather-faced Zapotecan Indians knew what it meant, and at that moment I believe they were as frightened as 1. They laid into the rope. The car moved on, and with a sort of sickening easy little crumble under that outside rear wheel-which I watched with my heart in my windpipe-and a final scrape of the already battered fender against the boulder, the automobile slipped beyond the crumbling dirt onto solid ground.

Ken flopped down on the rocky roadside. I dropped the block and tackle and walked around to join him. Arnold opened the door of the car and got out.

No one looked down the drop-off. Arnold just stared at the deeply scratched doors where the boulder had left its mark. And as the natives too, gathered around to look, he said with a quiet voice, his finger on the map of North America.

"If this was a New Deal car, Roosevelt ought to decorate us. We've scraped Maine and Vermont right off the United States!"

Relief was sweet.

"We got excited, didn't we?" I said, slapping Ken's knee. I left the boys with the men that day and traveled alone to meet Don Pablo, who would take me on to Tehuantepec to pick up more supplies.

The expedition near the equator.

It is fifty kilometers from Tequisistlan to Tehuantepec. And there is a kind of road for things on wheels! As Don Pablo and f speeded over the narrow, winding and difficult tracks in the Company "Camione"at twenty-five kilometers an hour (approximately fifteen mph) it seemed almost breathtaking. Actually to travel in a car for a full mile then thirty more on top of that without having to get out and work, move boulders, drag block and tackle, seemed wonderful.

In Tehuantepec we found very poor assortments of canned foods, groceries, and other items needed. Jucitan, a railroad center, was thirty miles farther and back toward the interior of the isthmus. We headed for Jucitan. With two hours in Jucitan, I bough: more groceries than I thought we could carry back up the mountains with only one burro, an additional fifty feet of 1-inch rope (to help us on the canyon wall of Rio Hondo), a 22-inch machete-and a pound of cheap, colored sugar candy. (It tasted like Christmas.) Then we started back for Tehuantepec. Night had already settled.

Setting up camp.

We stayed in Tehuantepec until next morning, then drove back the fifty kilometers to Tequisistlan. There Don Pablo said goodbye.

"I must stay here," he said warmly, extending his hand. "But I have given ample instructions. A man with two burros will accompany you up the mountain from La Mojada to where you meet the boys. You will also ride this mule. If you choose to come back with the man and work on this side of the mountain, I will give you six men to work with you. You could then build road back from this end, until you meet the car and the other gang coming from that way. You will stay in my camp, and need only pay, as we pay, for your food: a peso and a half per day (approximately thirty cents). What do you say?"

I wanted to get off the mule and hug my friend.

"You'll never know how grateful we are, Don Pablo. By all means, I accept. The boys can stay with the gang coming this way. I'll stay with your men. We should make contact in a few days."

"I give you two weeks to get here," he smiled.

"And I'll cut it in half," I said. "We'll be in Tequisistlan-if the car holds together-by a week from tonight!" It was Saturday.

I found the boys next day camped on the water's edge down in the depths of Rio Hondo's gorge. They had arrived there Saturday noon, spent the afternoon working on Z-turns up the canyon side, then called a day of rest for Sunday. With the natives, they were having a hunting, yelling and swimming vacation; good relaxation after the three weeks of hard work now behind them.

We fell to unpacking and I told of Don Pablo's offer for men to work the other side of the mountain, if I'd come back and work with them. Both Arnold and Ken agreed instantly.

"Anything to get us out of here," Arnold said, his face becoming suddenly serious. "I hold my breath every time I shift gears now for fear something'll explode in the transmission. There are some stripped teeth in it, I'm sure. We can't use reverse at all. And whenever I go into low, I get some awful clicks."

Somehow that sounded like bad news from a doctor just emerging from an operating room.

"What in the world would we do if the gears went haywire?" I demanded. "There are very few cars at Tehuantepec, or even in Jucitan. I'm absolutely certain we can't get replacements for a transmission this side of Mexico City. Anyhow, not for this job."

Arnold shook his head dismally. "Guatemala City's probably the nearest place we can get repairs. And I doubt this thing will hold together that far."

"There's plenty of hard trail yet to Tehuantepec," I said. "If the transmission will last to there we'll at least have a chance."

"How about this hill in front of us now," Ken demanded. "We'll need angels or sky hooks or something to get up that!"

I remembered the rope and dragged it from a box on one of the burro's backs. "This will help. When I passed here the other day, I knew we'd never get up with the rope we had. With this extra fifty feet, you can reach some of those trees growing farther away from the road."

"Swell," Arnold said, "I feel better already."

We fell to discussing the hill, the turns, the car, the men and the trail ahead to La Mojada.

"Once you cross the ridge above Las Vacas," I said, "there'll be fair sailing until you get into the canyon leading down to La Mojada. And if f have five or six men working with me we should have that in fair shape by the time you meet us."

"We'll need gas, though," Arnold said. "We haven't got more than about a mile to the gallon in these mountains. Too much racing of the motor, and spinning of the wheels."

"I made arrangements to get some up to La Mojada for us. But I thought we'd have enough to reach there."

"Better send it up with a native, tomorrow."

"Okay."

The groceries were unpacked and in the back of the car. I instructed the native who had come along with me, to pack my typewriter, my bedroll, suitcase, camera case, and a few other things, on the burro that had carried the canned goods, and then we were ready to start back. The men had all gathered around to see me off. We had paid them earlier, making a great ceremony of it, and now they wanted to wish me all kinds of luck on the other side of the ridge.

"Work hard, boys," I said to them as I climbed on the little mule. They laughed at my long legs in the short stirrups. "And if you get up this hill and across the ridge in three days, we'll have one 'gran celebracios when we reach Tequisistlan."

"Seguramente, amigo. Seguramente!" they chorused, and I pulled my mule's head toward the Z-turns up the canyon's side.

"Don't forget the gas," called Arnold.

"And don't let that transmission get away from you," I answered. "I'll have the gas up to you all right."

Next morning I sent of the 'mossos' of Don Pablo's borrowed gang, back up the trail with a five-gallon can on his shoulder. I've always wondered how he could climb that mountain with a load so unwieldy and so heavy. There were ten miles of steep trail. I couldn't help but feel sorry for him, but Don Pablo's assistant said he could do it easier than to send a burro with it. The following morning he walked into my tent at La Mojada with this note from Arnold.

"Sullies Thanks for the gas. We now have a quarter of a tank-almost."

When the roar of the expedition motor sounded down that canyon toward La Mojada Thursday noon I wanted to run up the trail to meet the gang. I was eating lunch on a rock in the shade, when I first heard the sound. I strained my ears to be sure I wasn't mistaken. Dropping my tortillas and canned preserves on the canteen, l stood up and shaded my eyes up the canyon for any possible sight of men or car. At last I saw it, and the six natives working with me must have wondered had I gone berserk. We were right at the crest of the worst turn and hill on the whole down-canyon trail.